Who Killed the 4th Ward Documentary

Who Killed the 4th Ward?

Commentary by Dr. Sucheta Choudhuri

Associate Professor of English

The title of this 1978 film—co-produced by Ed Hugetz, James Blue and Brian Huberman-- does two things at once: it prepares one for a celluloid elegy, and simultaneously sets the pulse racing with its unmistakable theatrics. "Whoever did it, we'll hunt him down," thinks a spectator fed on whodunits, and then shamefacedly checks her inner armchair vigilante as she recognizes the call to mourn the demise of a historic neighborhood in Houston. The subsidiary title ("A Non-Fiction Mystery in Three Parts") continues this duality, this complex interplay between history and histrionics. However, even the sobering signpost of "non-fiction" does not offer any certain, rock-solid answer to question posed in the film. As James Blue-- in a brief appearance early in the film—suggests, the film, at best, is a journey towards an understanding of the "forces" that control the destiny of a city and its people. This leads us to another question central to this cinematic narrative: "Can people without economic power have a say in the decisions which affect their lives?"

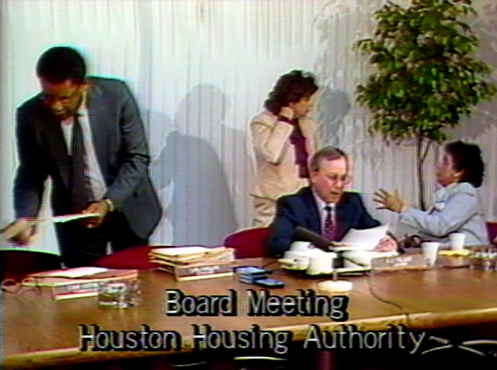

To this end, the film presents us with a series of encounters: with city officials,

business owners, and the inhabitants of the Fourth Ward. Established as one of the

one of four wards by the City of Houston in 1839, the Fourth Ward was also the site

for Freedman's Town, a community of slaves freed from the Brazos River cotton plantations.

Over time, the Fourth Ward was transformed into an epicenter of black professional

and cultural life, until its decline began in the 1940s. This gradual demise of the

neighborhood was precipitated by the expansion of Downtown and the building of Interstate

45, which pushed the more affluent residents out to newer neighborhoods. By the late

1970s—when this documentary was produced—more than half of the population of the Fourth

Ward was reduced to straitened means and dilapidated housing. We hear this loss echoed

repeatedly in the residents' interviews: the figure of candy-seller who bemoans the

loss of his livelihood becomes a compelling leitmotif in all three sections of the

film.  Despite the filmmakers' commitment to social justice, the film desists from offering

a neat solution. On the contrary, the form of the film lends itself to an articulation

of the messiness of the problem and the uncertainty about the way in which to address

it. Who Killed the Fourth Ward employs the techniques of cinéma vérité, a filmmaking style that not only approximates reality, but also features the filmmaker

as a participant/observer. We find James Blue slipping in and out of the diegetic

world of the film—supplying narratorial links in the form of a voiceover, in conversation

with his interviewees, pondering on the problem staring him in the face. But Blue

undercuts his authority with uncertainty; we see him buffeted by the dissenting voices

around him, voices that shift the responsibility of saving the Fourth Ward around.

Towards the end of the film, we find him—in a moment of meta-narratorial reverie—questioning

the adequacy of cinema as social intervention. Who Killed the Fourth Ward, then, leaves us with the larger question of the political function of cinema. Do

films do enough by simply drawing attention to disparity of social power? Should they

be doing more?

Despite the filmmakers' commitment to social justice, the film desists from offering

a neat solution. On the contrary, the form of the film lends itself to an articulation

of the messiness of the problem and the uncertainty about the way in which to address

it. Who Killed the Fourth Ward employs the techniques of cinéma vérité, a filmmaking style that not only approximates reality, but also features the filmmaker

as a participant/observer. We find James Blue slipping in and out of the diegetic

world of the film—supplying narratorial links in the form of a voiceover, in conversation

with his interviewees, pondering on the problem staring him in the face. But Blue

undercuts his authority with uncertainty; we see him buffeted by the dissenting voices

around him, voices that shift the responsibility of saving the Fourth Ward around.

Towards the end of the film, we find him—in a moment of meta-narratorial reverie—questioning

the adequacy of cinema as social intervention. Who Killed the Fourth Ward, then, leaves us with the larger question of the political function of cinema. Do

films do enough by simply drawing attention to disparity of social power? Should they

be doing more?