To Put Away the Gods

(Huberman and Hugetz, 1989)

To Put Away the Gods (mp4)

Commentary by Dr. Edmund Cueva

Chair of Arts and Humanities

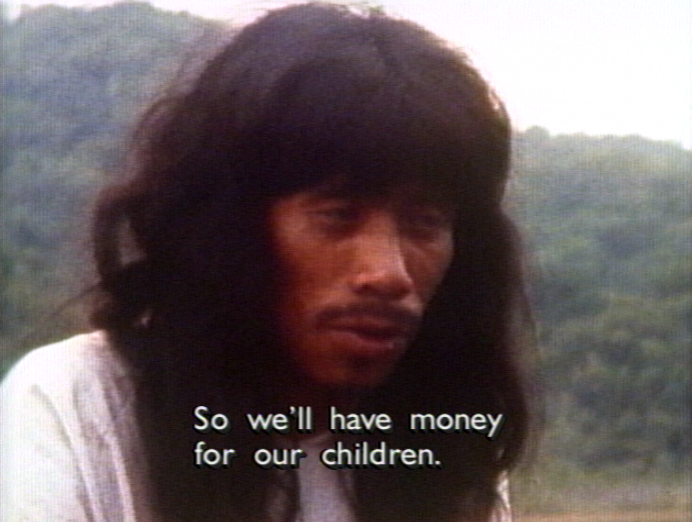

Huberman and Hugetz’ 1989 documentary, To Put Away the Gods, unintentionally shares its title with a passage from Joshua 24:14: “Now therefore

fear the LORD, and serve him in sincerity and in truth: and put away the gods which

your fathers served on the other side of the flood, and in Egypt; and serve ye the

LORD.” (King James Bible) Although the title was not selected from the Bible, the

biblical text can to some extent serve as a foil for the socio-religious changes taking

place in the documentary. The people of Israel were tasked to worship monotheistically

and to move away from the traditional practices created during their servitude in

Egypt, while the Lacandon Indians, as filmed by Huberman and Hugetz, have come to

a point in their cultural existence in which the younger members of that community

no longer worship their traditional deities. New attitudes are present among these

Mayan people—devotion and reverence to the old ways are challenged by the desire for

and acquisition of money and profit, by the intrusion of modern roads into their homes

in the rainforest of Chiapas, Mexico, and by the trucks that serve as one of the primary

means of communication and transmission between the new and old cultures.

Huberman and Hugetz’ 1989 documentary, To Put Away the Gods, unintentionally shares its title with a passage from Joshua 24:14: “Now therefore

fear the LORD, and serve him in sincerity and in truth: and put away the gods which

your fathers served on the other side of the flood, and in Egypt; and serve ye the

LORD.” (King James Bible) Although the title was not selected from the Bible, the

biblical text can to some extent serve as a foil for the socio-religious changes taking

place in the documentary. The people of Israel were tasked to worship monotheistically

and to move away from the traditional practices created during their servitude in

Egypt, while the Lacandon Indians, as filmed by Huberman and Hugetz, have come to

a point in their cultural existence in which the younger members of that community

no longer worship their traditional deities. New attitudes are present among these

Mayan people—devotion and reverence to the old ways are challenged by the desire for

and acquisition of money and profit, by the intrusion of modern roads into their homes

in the rainforest of Chiapas, Mexico, and by the trucks that serve as one of the primary

means of communication and transmission between the new and old cultures.  The Lacandon are not angered by these changes because they see it as part of the normal

cycle of existence and being: death, burial, and rebirth. It may be interpreted that

these events are merely part of the preparation for the putting away or burial of

the gods in the expectation and hope that these gods will return. This myth-cycle,

which is found in the Popol Vuh, the Mesoamerican myth-history that is sometimes referred to as the Mayan Book of Life or The Creation Story of the Maya, is also stressed in the documentary through its main character’s retelling of the

myth of the Mole Trapper Nuxi and his katabatic encounter with Kisin, the Mayan god

of death and earthquakes, and the god’s daughter. Not only do Huberman and Hugetz

capture the struggle that stems from the loss of long-established beliefs and practices,

but, most importantly for scholars and students of mythology, they record the ba’alche

ritual that serves as the enactment of the Mole Trapper Myth. This ritual-myth documentary

fits in well with E. R. Leach’ ritualist theory that “myth, in my terminology, is

the counterpart of ritual: myth implies ritual, ritual implies myth, they are one

and the same” (The Political Systems of Highland Burma [London, 1954], 13). Although this film needs a good preparation or background in

the complexities of Mayan myth and ritual before it is viewed, it can and should be

used in comparative or world myth courses.

The Lacandon are not angered by these changes because they see it as part of the normal

cycle of existence and being: death, burial, and rebirth. It may be interpreted that

these events are merely part of the preparation for the putting away or burial of

the gods in the expectation and hope that these gods will return. This myth-cycle,

which is found in the Popol Vuh, the Mesoamerican myth-history that is sometimes referred to as the Mayan Book of Life or The Creation Story of the Maya, is also stressed in the documentary through its main character’s retelling of the

myth of the Mole Trapper Nuxi and his katabatic encounter with Kisin, the Mayan god

of death and earthquakes, and the god’s daughter. Not only do Huberman and Hugetz

capture the struggle that stems from the loss of long-established beliefs and practices,

but, most importantly for scholars and students of mythology, they record the ba’alche

ritual that serves as the enactment of the Mole Trapper Myth. This ritual-myth documentary

fits in well with E. R. Leach’ ritualist theory that “myth, in my terminology, is

the counterpart of ritual: myth implies ritual, ritual implies myth, they are one

and the same” (The Political Systems of Highland Burma [London, 1954], 13). Although this film needs a good preparation or background in

the complexities of Mayan myth and ritual before it is viewed, it can and should be

used in comparative or world myth courses.